Prayer is scary; do it anyway

By Hilary White

First I must extend my sincere thanks to the kind readers and supporters of this site for their generous donations in the belated Autumn Funder. We have chased away the wolf from the door. I have asked a friendly priest in the US to remember the intentions of all who contributed in his Mass for the 1st Sunday of Advent.

And I particularly appreciate the little notes. I often doubt the usefulness of this sort of work. Having grown up on library books (with card catalogues) in the Time Before the Internet, I can’t shake the impression that the whole ephemeral thing is a bit frivolous and likely to one day vanish in a puff of ozone, taking all the work of the prime of my life with it into the oblivious void whence it came. Which would be a fitting end, I think.

Nevertheless, our site manager insists that thousands still visit every day (!!) and I receive not only financial aid but a small but more or less constant stream of emails and other messages from people telling me how useful it is to them. And thank God for them! I’m sure I’ve said before how odd it seems, spending most of my time in solitude, that there are thousands of people turning up daily at my invisible, virtual door. It makes me feel I should vacuum more often.

~

And now, to our divine causes.

~

I’m going to start with a big caveat: I’m not a theologian. Not even close. I’m just a regular schmoe, a person trained in nothing more than finding experts and asking them questions, and then making sentences about the answers in the sort of language other regular people can understand.

But I want to pray and pray more and pray better. And from what I’ve read in the last 20 years, while trying out activism, I came to think it’s actually the thing we’re all supposed to be doing. It’s the solution to everything. So I want to try to learn more and to share what I find out so other people can start doing it too. And maybe if we get enough people all doing the praying, that is, in the way the saints talk about it, something good might happen.

I know. It seems like a long shot to me too, but frankly nothing else works. Activism really isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, trust me. About the only thing it is really useful for is to have collected an extensive contacts list. I’m not a theologian, but I know a few.

Prayer is scary. As scary as saintliness itself.

It is easy to be intimidated by the notion of “living a life of prayer”. One looks at the saints, floating and bilocating and being unruffled by being flayed alive and whatnot, and figure they’re some kind of Special Humans. Maybe it’s like the spiritual equivalent of genetics or something; some people are just born to be superheroes. Whatever the answer, you know one thing FOR SURE: that ain’t you. And you mostly just pray, when you remember to, that you’ll be spared the apparent ravages and social embarrassment of excessive saintliness, telling yourself that maybe Purgatory won’t be that bad, and anyway is probably the best you can aim at.

One imagines, with a faintly superior and relieved horror, the trouble of learning Latin (or, with a shudder, Greek!) and even committing the entire book of the Psalms to memory, as was done by young postulant monks in the Middle Ages. Much of it seems obscure and remote, even foreign, entirely belonging to lost and forgotten fairy-tale ages; doing it all today is like installing a fan-vaulted chapel into a two-bedroom, vinyl-sided bungalow in Poughkeepsie.

Modernity backs us up on this, telling us we may have our religion, so long as we don’t take it too seriously. So we have exchanged – without a receipt – the humbling dread of the great, transcendent ascetic Faith of the desert saints and medieval mystics pursuing the Transforming Union for the comforts of an habituated weekly exercise in suburban middle-class respectability. The heights of mystical prayer – mystical union with Christ in this life – is not for such as us, and that’s quite the way we prefer it.

So far removed are we from this exalted heritage, that the saints aren’t much help. Personally, I find St. Teresa of Avila, with her complicated terminology of ways and “mansions” and rules, about as appealing as reading a calculus textbook in the bath. I’d be so worried about “doing it right,” remembering what to do next in the spiritual Order of Operations, that I would do nothing but worry about how to do it instead of doing it.

Is it any wonder that concocted modernist nonsense like “centering prayer” has so taken hold of the 1st World Catholic imagination? So much better suited to the suburbanite outlook. The prayer methods of the ancient mystics are difficult; so much easier to join the parish “charismatic” group and learn to yodel in auto-generated gibberish.

Even trying it is difficult.

It turns out that reading and writing about prayer is a good deal easier than actually praying. It is maybe this question which vexes and intrudes most. When a saint writes about the kind of prayer usually called “mental prayer” they make it sound the easiest thing in the world. Just a bit of reading, a very little bit, and then sit and think about it for a few minutes. Then remember your manners, and say thank you. Few of them addressing beginners like me seem willing to reveal that actually praying in this way is nearly always preceded by a titanic interior struggle; a combat with the will that I’m told is never truly won in this life.

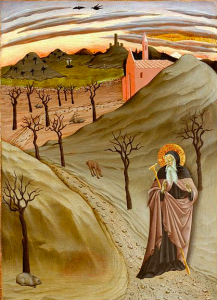

This, in part, is why the Desert Fathers referred to their life as “single combat”. For the great desert eremitical saints this combat was often tangibly and spectacularly fought with actual, visible, snarling demons, as related in the life of Abba Antony, the father of all monks.

But I expect that for the common soldiery, the lone monk in his mountain cave whom history, but not heaven, has forgotten completely, it is mostly the dull and tedious daily struggle with the self that occupies him. So efficiently do we block ourselves from union with Christ – a union that Christ Himself fervently desires – that it might be imagined the demon tempter hardly has anything with which to occupy his days.

A good friend, a nun whose job it is to do this kind of praying, told me once that the trying-to-pray part can occupy years, a discouraging thought. But she perked me up again by assuring me that God takes for Himself even the least hint that we are interested in Him. Trying to pray counts, at least a little, and He will use any little chink in our rusty armour to pour His unction. Not for no reason do the Psalms so often refer to grace as oil for the soul, always poured out in great and over-generous abundance.

So, what is with all the floating and bilocating and stigmata and all that, anyway? How did the martyrs make jokes during their gruesome deaths? How did the seven sons of the Maccabees, with manly cheerfulness, declare their preference for being tortured to death rather than betray God? How did Daniel, Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego walk about in the midst of the flames of the furnace of Nebuchadnezzar singing hymns of praise to the Lord?

All the saints say the same thing: mental prayer is the way to get this super-abundant unction, the way to become a saint.

But what is it?

“But what is it?” you ask the great Abba Antony, whose mountain you have climbed for a day and a night with great pains.

“Mental prayer?” he replies as though it is inconsequential. “Ah, nothing more than this: to think about divine things, to ask God for help and to thank Him for his gifts.”

You turn to St. Romuald, who has kindly agreed to accompany you on this visit, and ask if he knows what that means, that perhaps your translation from the great Abba’s Greek was inaccurate. What should you actually do?

He smiles and says, “Sede in cella quasi in paradiso.” Then adds, “Proice post tergum de memoria totum mundum.”

“Sit in your cell as in paradise?” you think. “Just sit there and pretend it’s already paradise? What possible use could that be?” Though the suggestion to cast from your mind all memory of the world is pretty appealing, considering what the world looks like these days.

These saints… you think, shaking your worldly little head. It’s as if they delight in being obscure.

Persevere, even if you’re no good at it.

But its clear that the people of our great heroic past had similar misgivings. They asked, as did the rich young man of Christ Himself, what shall we do to be perfect? When I was first re-entering Catholic life I remember having great trouble with the command, “Be perfect as my Father in heaven is perfect.” In the deepest most secret place of my heart I complained at the injustice of this; how was anyone to fulfil this completely impossible commandment?

Fortunately, the rest of the Catholic Faith is about and for instructing us in precisely that.

There is a little book, compiled many centuries ago, and that you can now download in its entirety onto your phone, called, “The Sayings of the Desert Fathers” that is full of the sort of thing Abba Antony and St. Romuald just told you. The “sayings” are little stories of young seekers asking advice of sage and tried old men. A young man leaves his family, gives away his fortune, and goes out alone to the desert to ask what he should do to be saved. The old hermit he finds in a cave there tells him, “Stay in your cell.”

Do your duties in life for love of God and for nothing else:

“There were two brothers in the desert who were the equals of each other I the spritual life, and they led a life of ascetic self-denial and performed the exalted works which belong to spiritual excellence. And it happened that one of them was called to be the head of a habitation of the brothers [a cenobium or monastery] but the other remained in the desert, where he became a man perfect in self-denial. And he was held by God to be worthy of the gift of healing those who were possessed of devils, and he knew beforehand the things which were about to happen, and he made whole the sick.

Now when he who had become the head of a habitation of brothers heard these things, he decided in his mind that his fellow monk must have acquired these powers suddenly, and he lived a life of silence and ceased from converse with men for three weeks, and he made supplication to God continually that He would show him how the monk in the desert worked these mighty works, while he had not received even one of the gifts which he had.

And an angel appeared and said to him, “He who dwells in the desert makes supplication to God both by night and by day, and his pain and anxiety ar for our Lord’s sake; but you have the care of many, and the consolation and encouragement of the children of men must be sufficient for you.”

And again, persevere:

A certain brother came to Abba Arsenius, and said to him, “My thoughts vex me and say, ‘You cannot fast; and you are not able to labour. Therefore visit the sick, which is a great commandment.’” Then Abba Arsenius, after the manner of one who was well-acquainted with the war of the devils, said to him, “Eat and drink and sleep, and toil not, but on no account go out of your cell.” For the old man knew that dwelling constantly in the cell induces all the habits of the solitary life.

And when the brother had done these things for three days he became weary of idleness, and finding a few palm leaves on the ground, he took them and began to split them up, and on the following day he dipped them in water and began to work [the monks wove and sold palm frond baskets for their living]; and when he felt hungry he said, “I will finish one more small piece of work, and then I will eat.” And when he was reading in the Book, he said, “I will sing a few Psalms and say a few prayers, and then I will eat without any compunction.”

Thus little by little, by the agency of God, he advanced in the ascetic life until he reached the first rank, and received the power to resist the thoughts and to vanquish them.

~

Tomorrow we will hear from Dom Bede Frost, late of Nashdom Abbey, Burnham, Bucks, about the “Catholic tradition of prayer, in which Being and not ‘doing’ is the all-important thing,” and why it is necessary for modern Catholics to renew this spirit; and from St. Romuald and his student Bruno on how one may acquire it.

~